I must confess I’ve never met Marfa but she visits me in dreams at least once a month. Visions of Judd’s concrete monoliths dance in my head.1 The prophecies have never been clearer: I’m meant to make pilgrimage there one day . . . I’ll hit the road with a friend, hot wind whipping through our hair as we sip Mexican Cokes out of glass bottles from a lonesome faded gas station on an open stretch of desert highway. In this scene, a tumbleweed should probably roll by — to really drive the point home. All the while, Ry Cooder’s slide guitar twangs languidly in the background.2 Perhaps another dream will instruct me when to start packing.

These scenes are easy to conjure for me, and even easier to love. The dryness in the air once you cross the California border headed west alone will do it for me. It shuffles up memories of our biannual family road trips to my uncle’s ranch on the outskirts of Tuscon, in a ghost town aptly named Oracle. Nothing much but towering rock formations and alienesque cactus3 for miles until you hit what feels like the end of the earth (or the base of the Santa Catalina Mountains).

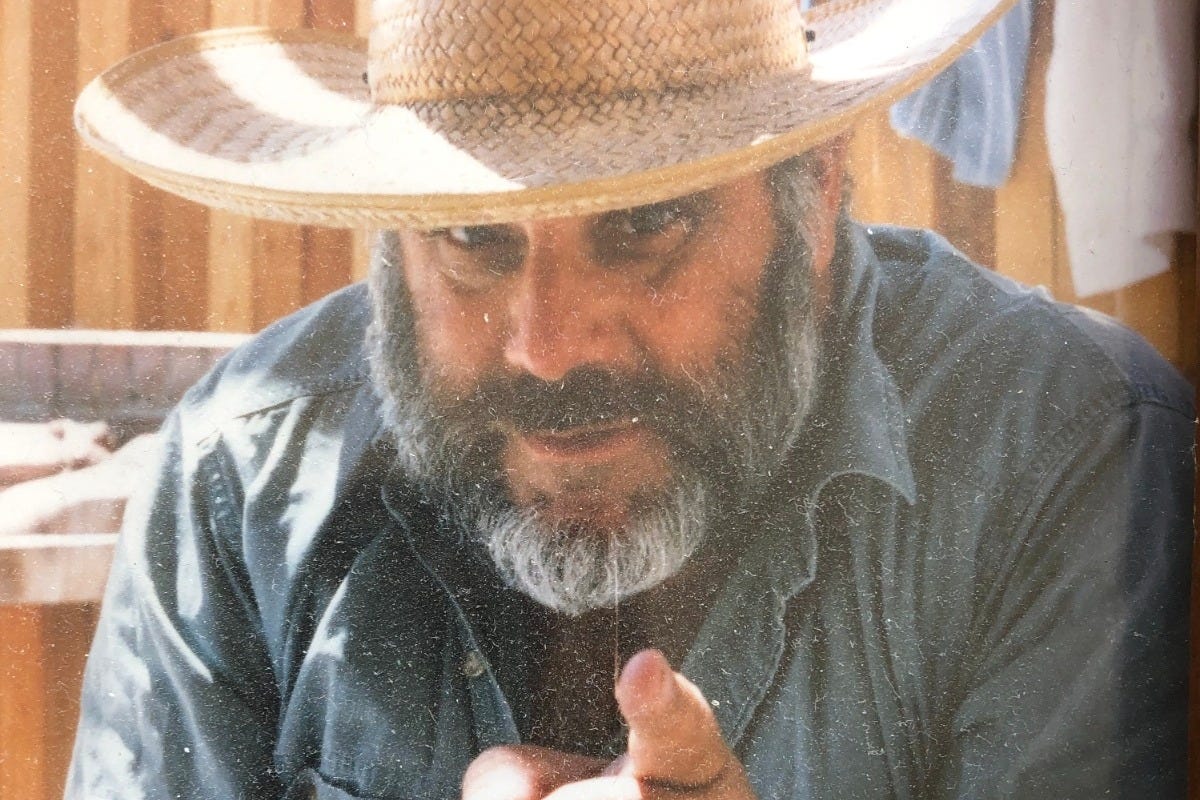

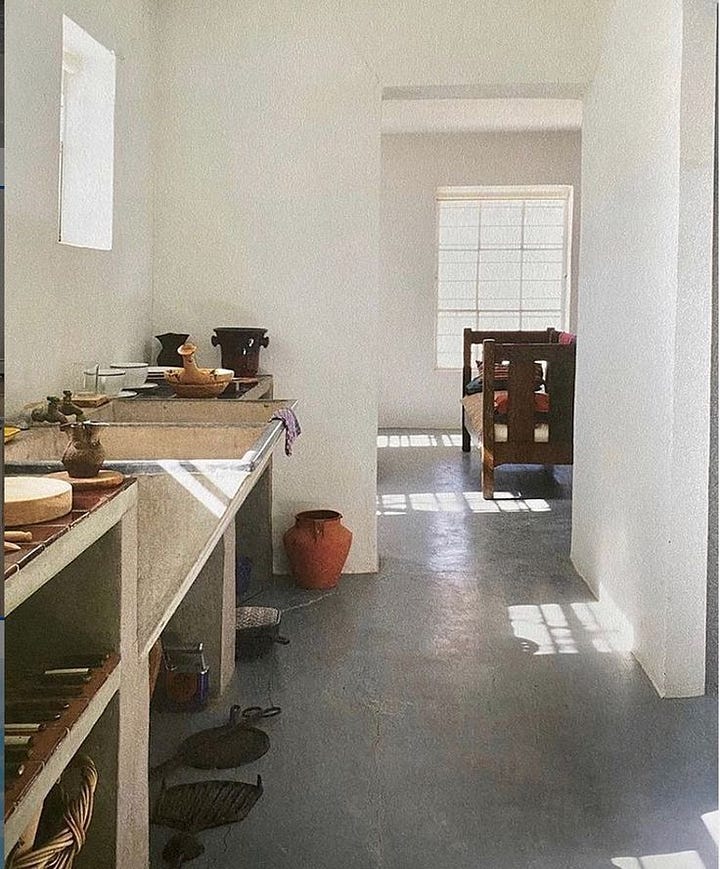

Once a certified beatnik (he’d hang in The Haight with Ginsberg but “never really liked the guy”), turned Texas-trained carpenter, turned Arizonan rancher, my Uncle Steve bought a run down ranch on 32 acres in the early 80s. There, he built 26 traditional adobe casitas and painstakingly restored the barn and grounds far beyond even their original glory. He filled the rooms with local art, wrought iron lamps, hand-painted Mexican Talavera tiles, punched tin mirrors, Equipale chairs, and indigenous tapestries on the beds and walls. Armed with the insight of local tribesmen, he dug and built a complex well water system to supply the whole ranch.

Steve brought his dream to life with his bare hands; very few can say the same. What he lacked in business acumen, he made up for in charm. So he ran the ranch like a sort of retreat center — it was, at times, an artist commune, a sanctuary for hippies embarking on spiritual Ayahuasca journeys, a site for UFO hunting expeditions, a center for environmental activist summits, and a gathering place for wholesome family reunions.

My uncle welcomed one and all to experience the fruits of his labor. He famously hosted a grand Thanksgiving for our family and friends every year. His eccentric artist friends, and their friends (and occasionally, the homeless man he befriended at the grocery store the day before) would flock to the ranch in droves. Year to year, the plein air painter or the metal sculptor would bend over and whisper things like: “You have the most beautiful, sad eyes, little girl. Anyone ever tell you that?” That was my cue — my cousins and I would run off to play poker by the fire while the adults drank wine and filled the dining hall with roaring laughter.

My uncle would conclude dinner by reading one of his poems, and after her passing, he’d read the one he wrote in memoriam of my beloved aunt.4 Though we’d heard it many times, there was never a dry eye in the room. His gift of poetry is so natural, you feel as if the words came from within yourself. Then, my other uncle, once “Emmy award winning” composer turned nomadic new age musician (after a series of poor financial decisions), would play the piano and we’d all clap and sing along and dance the night away.5 My warmest memories of the ranch were born from those gloriously offbeat holiday gatherings. The music and poetry imprints on the soul.

Of all the artists and poets who stumbled onto the ranch, I secretly always held out hope that one day James Turrell would waltz in. It’s not too far off — he’s a proud Arizonan after all. He erected a temple of the sky on the state college campus, and spent decades carving a stairway to heaven within the crater of the Roden volcano6. Nevertheless, we had our own Turrell experience — in the childrens’ smiles, in the perfect blue sky that unfolded each morning, in the stars glistening across the indigo night… the moon’s glow seemed to line the mountaintops in silver. The ranch too corralled a powerful light.

During law school, I would flee from the library and nightmarish final exams to visit the ranch. As I hit the road, I’d fantasize that I would drop out and never return (of course I graduated with honors). I actually looked forward to the 7 or so hours of driving alone with my thoughts; of speeding down the desolate highway hugged by the mountains, pastel sunsets silhouetted by power lines, fluorescent lit gas stations where truckers would squint at me — with my shiny California plates and my even shinier California aura — while I filled up and avoided eye contact. As night fell, I’d tune the radio to devastating western ballads, like “Haunted After Midnight” and “16.88” by Slim Martin and Hayden Thompson, to get into the spirt. The electric baritone of those lonesome cowboy crooners always takes me there: to the scorched earth of the broken heart, to revisit the yearning for a lost lover . . . . Maybe it’s masochistic, but it makes my heart flutter.

At sunrise, a forest of Saguaros would greet me, their arms stuck in a permanent wave. Sometimes they’d even have big yellow blooms at the ready, a real treat for the eyes. Warm welcomes like these restore my childlike wonder. As soon as I pulled up to the ranch, I’d turn off my phone and tune in to the desert. Sometimes, a blessing looks a lot like no signal. My uncle and I would take the days slowly, drive the truck down dirt roads, meditate in the Saguaro forest, pay respects to the roaming wild cattle, head down to the border for tacos and cervezas, admire the laughter floating through the air from a neighborhood fiesta.

At dusk, we’d return to the ranch for our nightly ritual — play poker by the fire, read each others’ tarot cards, stretch out on chaises to stargaze and take in the symphony of the desert — coyotes crying, Javelina rustling in sagebrush, the cool wind reverberating through the hills. To some the desert is a dead thing, but the desert is very much alive for those with eyes to see.

“Despite its clarity and simplicity, however, the desert wears at the same time, paradoxically, a veil of mystery. Motionless and silent it evokes in us an elusive hint of something unknown, unknowable, about to be revealed. Since the desert does not act it seems to be waiting—but waiting for what?” — Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire (1968), Tucson, AZ

Arizona may be the birthplace of my Americana awakening, but the vast country calls to me, beckons me to dive deeper. So much of the southwest is untapped territory for me, including the mecca of all, Texas. Tucked away, Marfa seems, from afar, a western playland where modern art and the wild west unexpectedly intersect, coexist even. It’s not at all dissimilar to the ranch, which was a wondrous microcosm of the same principles. But that a place like Marfa became a magnet for noncomformists and creatives should come as no surprise. Bohemia is a state of mind which thrives in the plain open space of the high desert.7

"They speak about Marfa with the same kind of reverent tones generally reserved for the pilgrimage of the Virgin of Lourdes." — Carolina Miranda

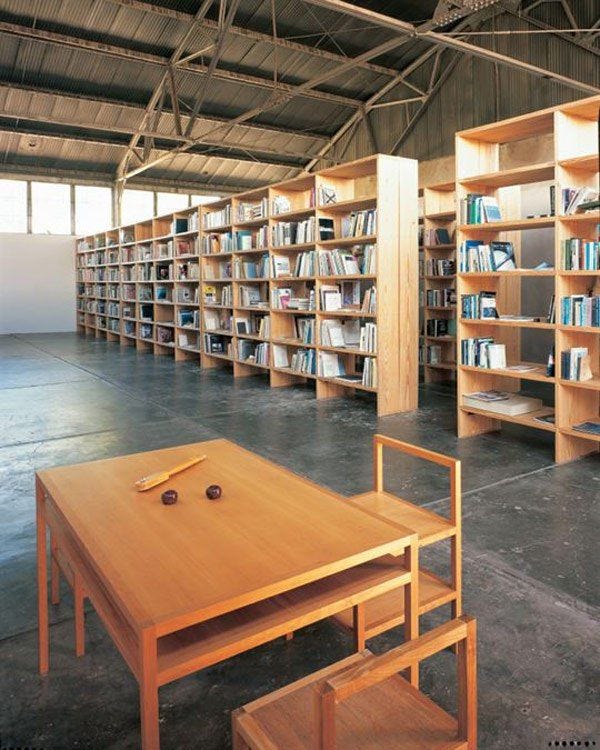

I often lust over the idea of seeking refuge from the dry heat in Donald Judd’s minimalist — only in appearance, not volume — library. I’d breathe a sigh of relief, wipe the sweat from my brow, and slink into one of his rectangular wooden box couches with a big art book til sundown. Such is my personal heaven. And listen, I’m not immune to the allure of a funky hipster camper van park called El Cosmico.8

Marfa’s rules come through clear as the blue sky: LESS IS MORE. The desert is never really what it seems. One must flirt with the mirage to appreciate its boundless glory. Judd’s hard, sharp forms ground you in the immediate space, but in their simplicity, command you to notice the details, to inspect the subject from every angle, to take a long hard look, to see within and without. Absentia always triggers the imagination more than stimuli. The clean lines draw your eyes to the ground, to the horizon, and finally, to the infinite great beyond. At first, nothing, then everything unfolds before you, just as darkness gives way to the light of day.

I can picture myself wandering among Judd’s concrete and steel sculptures framing the one dimensional desert landscape, portals that beckon you to cross the threshold, to enter the void. Whereas Turrell bends light to inhabit space, Judd forges space through metal and wood. Both channel pathways for lightness and darkness through angular, self-contained forms. They harness that which denies to be contained, and in doing so, emphasize the wildness, the ephemerality, of nature.

The works serve as a reminder that we are ultimately at the whim of the universe, of the great unknown, no matter how hard we try to manipulate, conform, or otherwise make sense of it. We may ask: Who owns the invisible sky? The phantom light? Well, the truth is, it belongs to no one, but for a split second, Jim and Don may be able to capture it for your eyes to (be)hold.

Perhaps, to answer to Abbey’s burning question:

The desert is waiting to be caught, to be seen.

Honorary Mentions:

I would be remiss not to mention the mythical “pop architectural land art project” Prada Marfa, from the minds of Elmgreen & Dragset.

Every small western town carries rich extraterrestrial lore. Enter the Marfa Lights: mysterious orbs that float over the Chinati mountains at night and evade scientific explanation. (As they say in The X-Files) “I want to believe” that this is not another small town’s scheme for a tourist trap. My uncle’s ranch lures world renowned UFO investigation groups who meditate beneath the Saguaros in hopes of channeling aliens who access the earthly plane through mountain portals. I even found a video from one of their “expeditions.” My Uncle Steve makes several cameos, and makes a comment on the sightings at 1:16) One man even claimed that an E.T. visited him at the ranch, touched his head, and cured his terminal brain cancer. Stranger things have happened in the high desert.

Dedication:

To my Uncle Stephen. Who else? For being my closest confidant, for building a sanctuary for all, and for introducing me to the magic of the desert. Love you, Steve. Though the ranch is no longer yours in name, it will always be ours.

To Listen:

Footnotes & Additional Research:

Referring to Donald Judd, 15 untitled works in concrete, 1980-1984. Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas. See here.

My Uncle Stephen published a book— A Whole Town in Slippers — a collection of poems written during a fifty-year period of self-imposed exile in Galveston, Texas and Tuscon, Arizona. Most of the poems revolve around various states of time warp, a condition necessary for the author to both write and perform his poems and stories. The time warp takes the form of a whole town in slippers, or what the author calls speeding in the slow lane.

My (other) uncle composed the famous theme song for the 1987 TV series, Unsolved Mysteries.

I love this stunning, meditative short film featuring James Turrell, touring his Roden Crater project and poeticizing the light.

Both Tuscon and Marfa are located in the high desert regions, the Sonoran and the Trans-Pecos, respectively.

See El Cosmico. Places like this are a plenty there, but people seem to have moved on to “The Next Marfa,” wherever that may be. I’m just pleased it’s no longer sceney (we have enough of that in LA).

See also: Marfa Texas: An Unlikely Art Oasis in A Desert Town